In early June during a weekend on the other side of Lake Michigan, I visited the Art Institute of Chicago – a museum that I was lucky to frequent as a kid during family visits to the city. No matter how many times I’ve been there since, each time I walk up the steps between those giant bronze lions, I am instantly nine years old, enveloped in a sparkly golden-hued childhood memory cloud. When I first laid eyes on Monet’s glowing haystacks, Degas’ dancers, Seurat’s pixelated Parisian park-goers, Hopper’s lonely night cafe, O’Keeffe’s looming flowers, I sat on a well-worn gallery bench, awestruck to just be in the same room with paintings that I’d only previously seen in books. Even as an adult I’ve never really shaken that feeling. There is nothing quite like being within inches of these special objects that have traveled through time to tell us stories. Return visits always yield a new perspective.

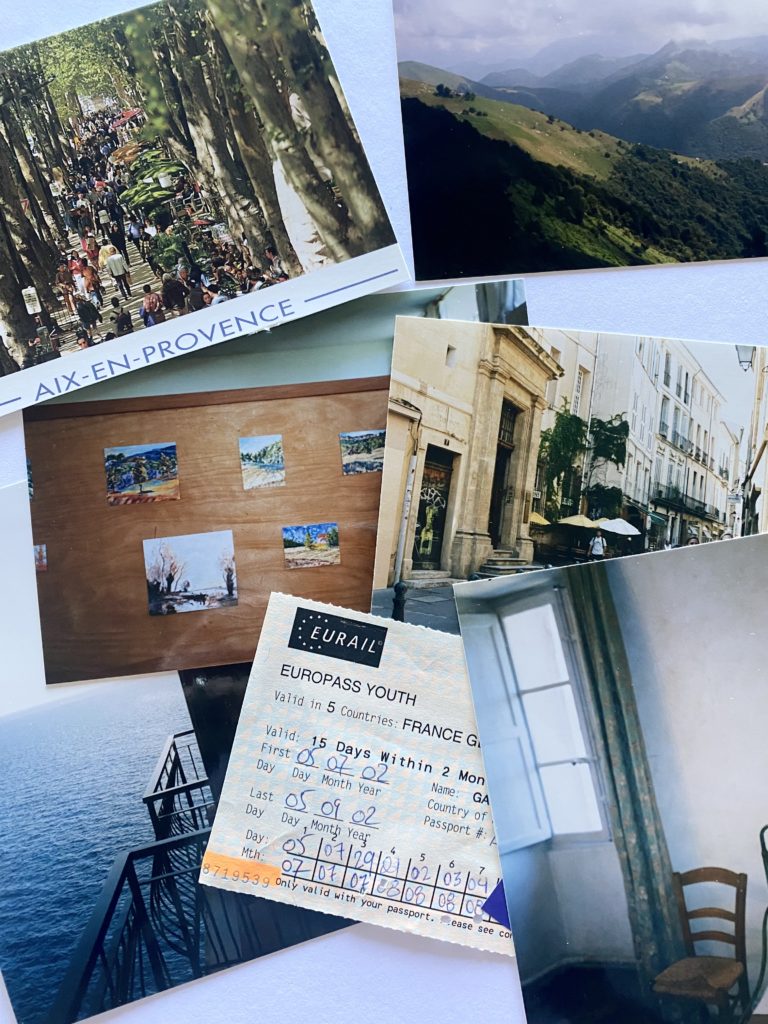

I was lucky to visit AIC during the museum’s current Cézanne retrospective. Seeing the show, I was transported to another June twenty years ago. That summer, I had chosen to study abroad in Aix-en-Provence at the Marchutz School where, like a daydream, I would paint en plein air in the sun-soaked fields skirting Cézanne’s beloved Mt. Saint Victoire.

Wandering through the galleries, it wasn’t Cézanne’s famous landscapes that brought me so vividly back to my 20 year old self. Instead, it was a few waist-high glass boxes containing his small sketchbooks and watercolor palettes that drew me in. Looking at them felt remarkably intimate; the sketchbooks filled with airy, overlapping drawings of trees and gardens, of his children, his home and scattered domestic objects. His palettes were messy with dried pools of color, as if the water had evaporated just moments before. These were vestiges of Cézanne the person – the tools he held closely, used to work ideas through and get them down on paper as life was speeding by around him. The pages showed fluidity and effort at once. They were vivid windows not just into what he was seeing, but how he was looking.

One idyllic day that summer in France, our class was painting near a creek under arched trees lending their canopy of dappled light. I was attempting to capture that perfect light as it skipped around on the water. It was beautiful, it was moving fast, and it felt practically impossible to capture. I wanted so badly to match the abundant beauty of the moment in my drawing, but every time I tried to get it down, I’d look up to find that what had been before my eyes moments earlier, had already changed. How does one capture constant change in a single drawing? It’s a question that has haunted me since.

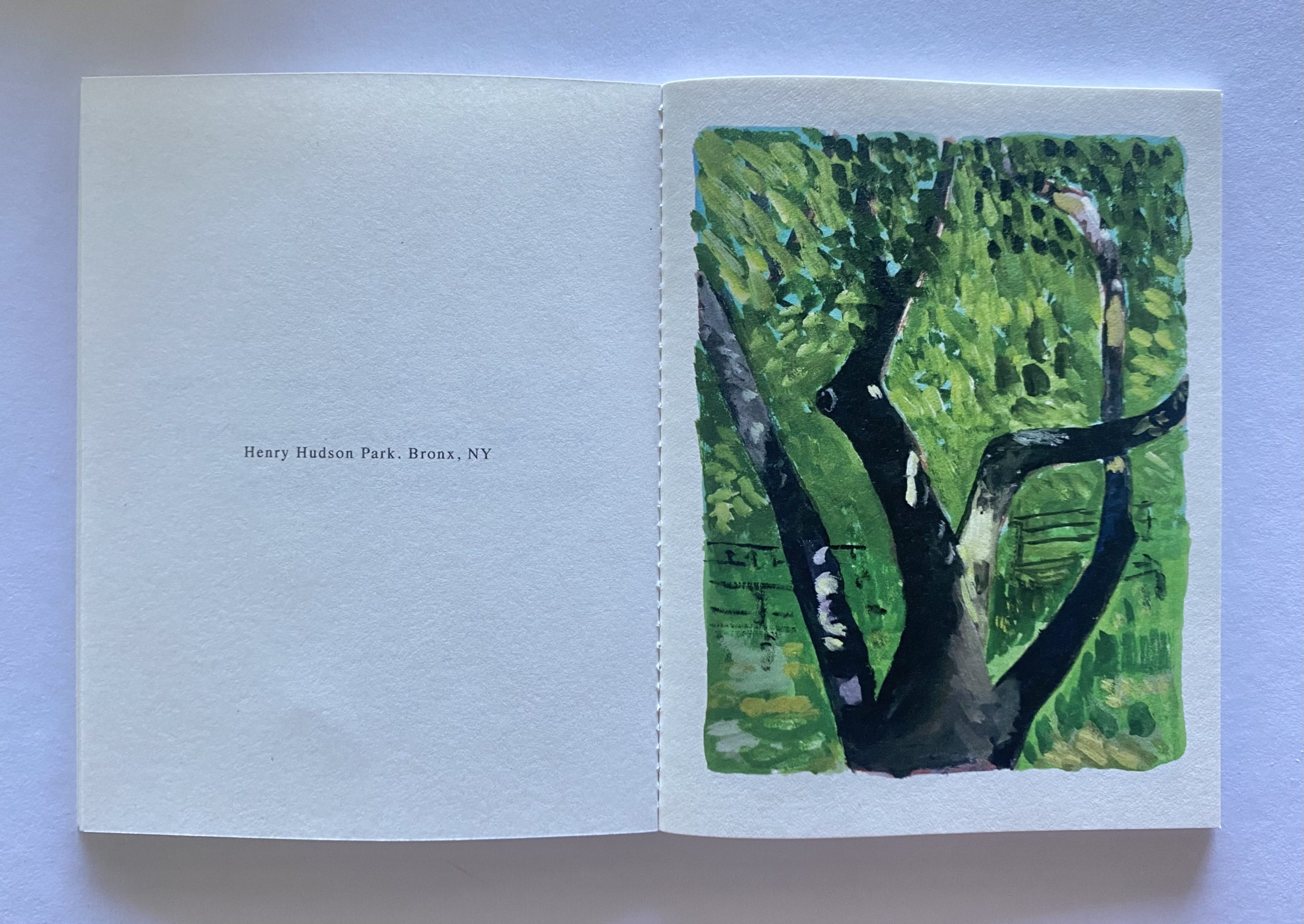

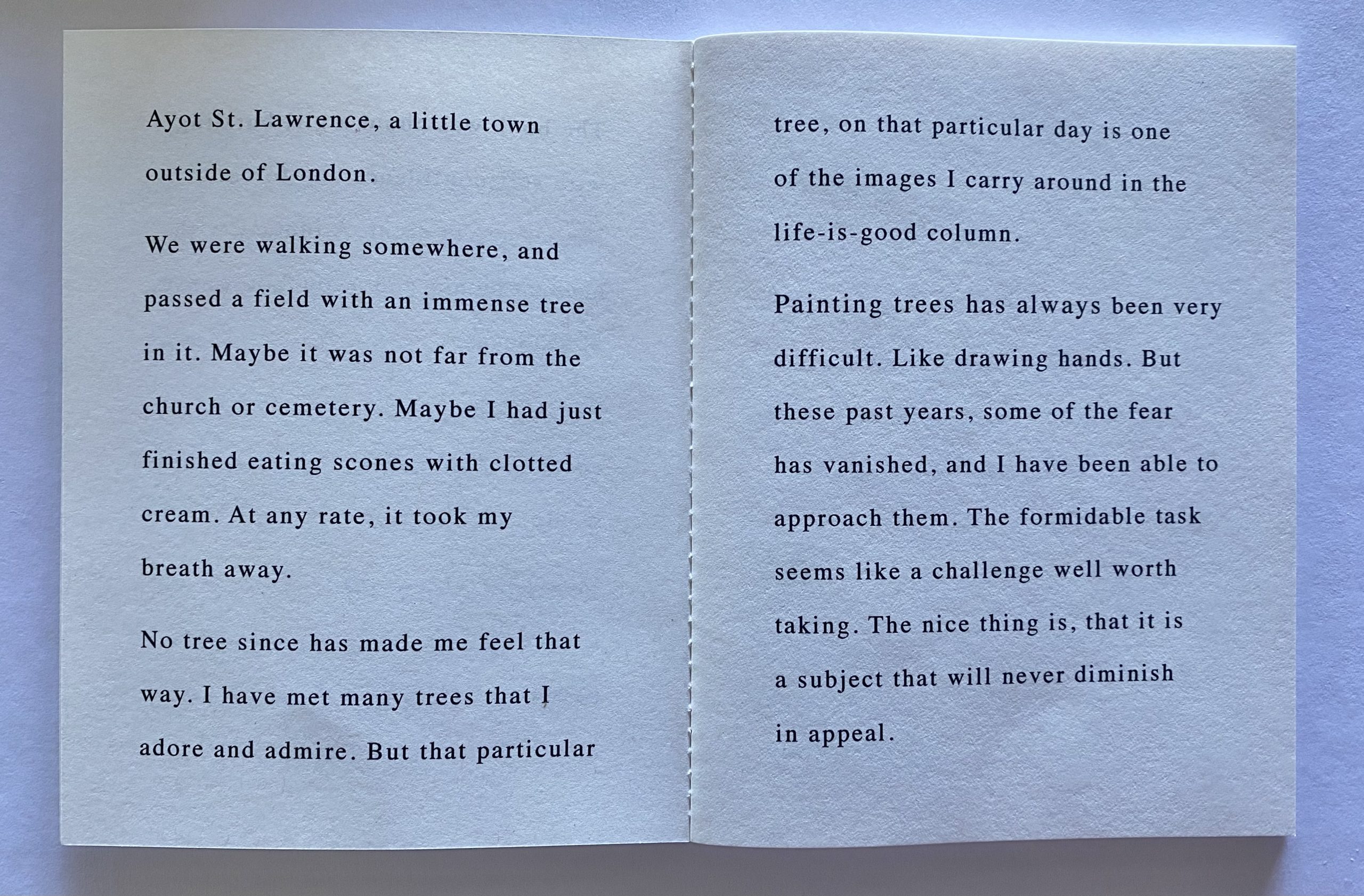

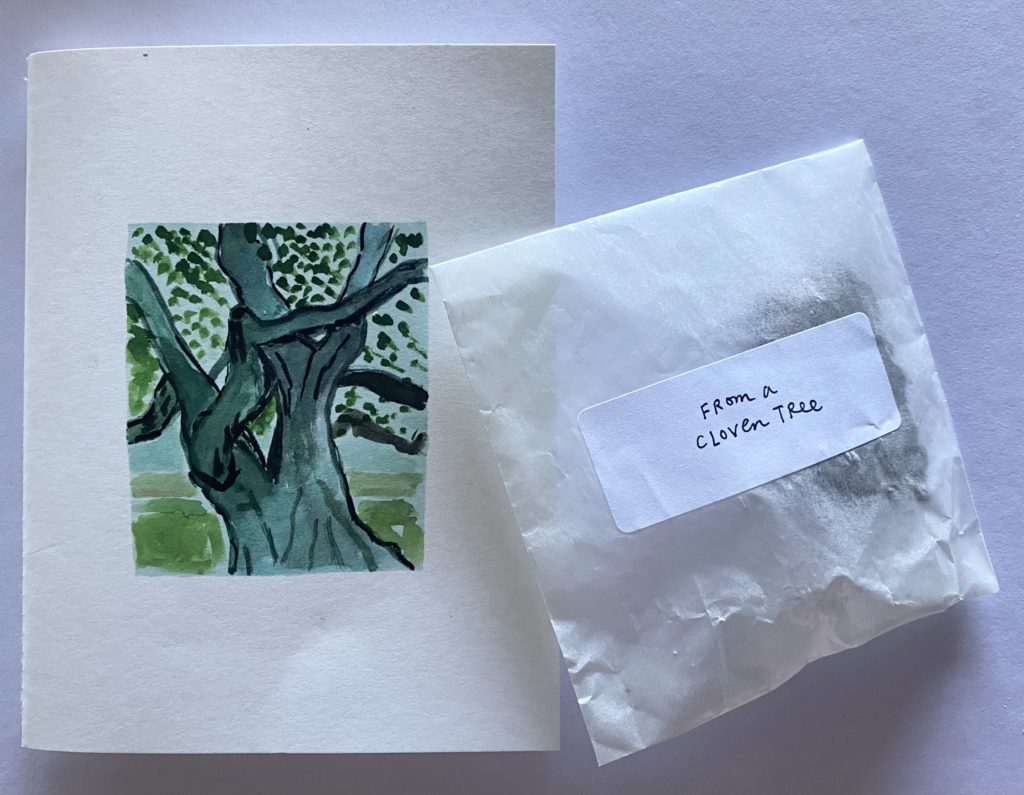

Two years ago, mid-pandemic, in the months leading up to the 2020 Presidential election, one of my art heros, Maira Kalman, sold a limited-edition booklet about trees to raise money for a grassroots voting organization. Each one came with a half-dollar sized piece of bark from a cloven tree. I was lucky to get one before they sold out, and thrilled when the small package arrived in the mail a few weeks later. In the opening pages, Kalman writes about a childhood moment sitting under a special tree when she knew that she would write stories, then describes another tree moment years later that has always stuck with her. She continues:“Painting trees has always been very difficult. Like drawing hands. But these past years, some of the fear has vanished, and I have been able to approach them. The formidable task seems like a challenge well worth taking.” In a moment when the world could not have seemed any darker, this small collection of tree paintings landing on my doorstep felt laden with hope. It was a talisman for better days to come, and a palpable reminder of the value of stopping to look, to draw, to simply notice and record the magic when you feel it. Even, and possibly even more so, when the act might seem so small amid the currents of a tumultuous and frenetic world.

A few months later in Spring 2021, when we were all still firmly ensconced in pandemic times, I tuned into a conversation between Wayne Theibaud and Lois Dodd hosted by UC Davis’ Manetti Shrem Museum of Art. Theibaud was 101 at the time, and was Dodd 94.

During the talk a student asked Dodd if she ever goes back into her work after she’s finished a painting session. Her immediate answer was: “I’m different the next day…I can’t go back.” Dodd has made many of her paintings outside over the course of her life, rain or shine, with small masonite or aluminum shingles and her paints in tow. She works fast, capturing what she sees in front of her in a single painting session because, as she remarked in that 2021 conversation, “Nothing is the same more than once.”

Our subjects are always changing, and we are ever changing. So can we ever go back? In a way, I think this question links these two artists whom I so deeply admire to Cézanne’s driving impulse. Like Maira Kalman’s hopeful book of trees and Lois Dodd’s steadfast observations of life-as-it-is-right-now, Cézanne’s sketchbooks reveal a profound sense of urgency. The three share a laser beam sensibility to look, see and record the essence, the feeling of a moment. Then move on to do it again and again, because nothing is the same more than once. It’s impossible, and wonderful. For what would the world be artists’, poets’, writers’, dancers’, and singers’ sincere insistence on trying? The challenge is, as Kalman writes, “well worth taking.”

ADD A COMMENT